SPLIT AT THE ROOT

In the previous chapters of Leah Napolin’s novel, you were introduced to Temple Beaupre’s grandfather Eugenie who narrates certain chapters of this story, and, via Temple’s memory, you met her and Fannie, the family’s housekeeper. You encountered Laurette Limley, Florida Penrose, and Mavis True: three women “who shoot birds.” And, you learned about Temple’s mother and grandmother: two women who definitely did NOT shoot birds. You shared a “sleep-over” at Sally Ann’s and heard how the Stotes said good-bye to their outhouse, and were witness to a real “Family Feud.” Temple has let you in on some further family secrets and how she began to move within the South’s “traditional values” and these dark secrets that lead to her encounter with Slade Fontenot and a notification of a family loss and the funeral. Eugene lets you in on more of his surprising history, while Temple confronts an unpleasant reality that is emphasized when both LuEsther and Temple are “clubbed” with secretive family background and white sheets, and this leads to even more questions. Providing more family details, Eugene tells a blood curdling tale. He and Temple continue to let you in on tales and secrets of their family with a special view of Mam.

Part 1 of Chapter 23 involves Temple’s adventures with Erskine and his Cadillac.

Chapter Twenty-three, Part 1

FREAKS OF NATURE

"A Reverend Thompson arrived in our town to lecture on temperance. The Hall was reserved and handbills distributed but not half a dozen persons showed up." - Zenobia Bugle, November 15, 1850

TEMPLE

Erskine Buford was a dapper young man just out of school and starting work as a livestock veterinarian for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Field Station #4, Creek County, Mississippi, when he married his first cousin twice removed, and Parmelia Meacham's youngest sister, Mary. It was a love match. Mary Temple was Mam’s favorite sister, and Erskine the brother-in-law Mam doted on above all others.

Erskine wore straw hats and his watch on a fob. Erskine loved to read-—ancient Greek history, Longfellow, and could quote from memory a number of Shakespeare sonnets. Wherever Erskine went he carried the sunshine with him, usually in a flask with a silver stopper. Wild, improbable things attributed to him were talked about long after they happened. Remarks he is supposed to have made continued to be quoted long after he said them. However, by the time I was old enough to know and appreciate the hero of so many stories, the hero had vanished and in his place was an ordinary man. People said he had mellowed. Maybe the word should have been "melancholy'd."

Figuring prominently in his sorrow and the drowning of it were two things that happened before I was even born. The first involved Mary. As a child, Mary suffered from rheumatic fever which weakened her heart, which she further taxed by carrying to term a pregnancy she'd been warned against. But she was a willful girl and determined to have this baby, their first. The child, a boy, was named after his father. Mary died not long after giving birth, like Helen Tully, my natural grandmother. There were pictures of Mary Temple in Mam’s photo albums. She was very beautiful. I wish I’d inherited more than just her name.

When Mary died, Erskine went half mad with grief. He blamed himself for the pregnancy that had taken her life. But the family refused to accept his guilt and punish him for it. They felt he had suffered enough.

After a decent interval of time, Erskine remarried—-a socially prominent widow older than he, who added his motherless child to her own brood. In those days he came to Zenobia often, to visit, sometimes bringing his second wife, Dorthy (Dot) Wilkes, and all the children, with him. Even though Mam continued for years to mourn the death of her youngest sister and tried to keep her distance from "that woman who took Mary's place," they grew in time to be close friends. Parmelia Meacham and Dot Wilkes actually had much in common, being church-going ladies of strong conviction.

Erskine, Jr. grew up with his father's sandy hair and mild, deep-set eyes. When the war came, the boy lied about his age in order to enlist in the army, and was killed months later by a land mine among the hedgerows of Normandy. Erskine took to the bottle again and never let go.

No one would go so far as to suggest that Erskine's marriage to Dorthy Wilkes was a love match, as had been the case with Mary Temple, but it was a good one in many respects. Dot, known for her high moral principles, "kept him in line," as Lu-Esther would say. Devoted to his wife and family, Erskine behaved himself for Dot's sake. Yet, this exemplary public demeanor always appeared to be somewhat counterfeit, as if there were a younger, more impetuous self submerged just below the tide line of habit. The strain of being good, everyone assumed, must have been considerable.

Erskine was Lu-Esther’s favorite uncle and mine too, because he was the first to put a book in my greedy little hand, Bullfinch’s Mythology, the first to read aloud to me and feed that great hunger for stories--real stories, made-up stories, any kind of story. Erskine pretty much taught me everything I knew. How to fish and hunt. How to drive a car. By just keeping my eyes and ears open I also managed to imbibe a lot of smoking, drinking and cussing lore. Other things, which shall remain nameless, I picked up on my own.

Erskine drove an old Cadillac Fleetwood that he maintained with all the spit and polish of a regimental staff car. When we drove together he was the general and I was his aide-de-camp. All that was lacking were little flags fluttering on the front fenders.

What I liked least about the Cadillac was its smell. Since, by decree of Aunt Dot, smoking was not permitted in the house, the Cadillac became Erskine's club on wheels. When he drove, there was usually a lit stogie or cigarette clamped between his teeth giving out clouds of smoke like a locomotive, ash falling everywhere. He seldom emptied the ashtray, and joked that what he needed were windshield wipers on the inside of the car. Miss Dorthy had him drive with the windows open, no matter what the weather. Uncle Erskine smoked only the best: hand-rolled Cuban cigars and unfiltered Player's in their handsome little hard packs, which were shipped to him from a tobacconist in New Orleans.

What I liked most about the Cadillac was the burled walnut dash, the cracked leather upholstery that squeaked when you sat on it, and the trunk. Yes, the trunk. Besides the jack, the tire iron and the spare wheel, there were always interesting things in the trunk: lab specimens, telescopes, fishing tackle, lab specimens, duck decoys, anatomy books and books of poetry and, even, a deer rifle. And lab specimens.

In the glove compartment of the Cadillac Erskine carried a silver thermos. If he was going somewhere with Aunt Dot the thermos would be filled with hot black coffee. If he was going someplace without her, it would be filled with a specially distilled 200 proof pure grain alcohol that one of his lab assistants in Bristow cooked up for him. This he called his "tea." He had bottles of "tea" stashed everywhere, including the dry well on the grounds of their house in Bristow. I was once given a taste of it and, oh boy, it packed quite a wallop!

By hiding the evidence of his vice so cleverly and masking the telltale clues with tobacco smoke, Erskine was convinced that he'd spared his wife not only the heartbreak of exposure to alcohol but also the true dimensions of his drinking problem. Everyone assumed that Miss Dorthy knew and just looked the other way. She was very smart at letting him think he was getting away with something.

Uncle Erskine appeared at our front door in Zenobia one evening, unannounced, on his way back from a livestock show at the Okabigbee County Fair, and invited me to drive the rest of the way home with him to Bristow to spend the weekend. Dorthy's children were grown by then with families of their own, and frequently the house was filled with Bufords and Wilkeses of all ages, a lively mix I enjoyed. I liked Aunt Dot, but the real enticement for me was time spent with Uncle Erskine.

In some ways he was an enigma: a man who was high-spirited yet moody (you never knew which Erskine you might encounter on any given day); a man who could be shrewdly calculating or play the fool; the hard-drinking man of action who cultivated a secret life of the mind. His contradictions made him interesting to me, his losses made him tragic. But he bore these sufferings in private in the far reaches of his soul, where even those who were beloved of him were not granted admittance. Still, something about him touched a responsive chord in me. We were both reckless and fun-loving. Misfits and rebels. There was an unspoken kinship between us.

Since Mam was also visiting in Bristow that weekend (she and Dorthy had discovered they had more in common than Methodism—-they both loved to shop) it was agreed that I would drive up with Uncle Erskine the next day and return home Sunday night with Prater and Parmelia.

"Come on, T'tée," Erskine said, "let's go see the world."

As narrow as my world had been up until then, I didn’t find it at all confining. First, there was the bewitching city of New Orleans, where I’d lived the perfect life of a child of privilege. And then there was Zenobia. There was the inner world, which was the world of books and daydreaming, and the outer one, which was the world of nature.

It was the country pleasures of Zenobia that I preferred, hands down. Pleasures that didn't seem the least bit limited by the one square mile of sleepy town and the fewer than 1,500 souls who lived in it. Besides the town and my favorite haunts in it, I also had the woods, fields and marshes that stretched for miles on every side, and the winged and four-legged things that lived in them. Without a single wistful look back in the direction of the house on Harmony Street in New Orleans with the bronze deer in the goldfish pool, I gladly exchanged the make-believe one for the real thing, a legendary blue stag that roamed Black Tom's Swamp. My ambition was to hunt that stag.

Then, once a year during the hottest part of the summer, the Beauprés exchanged the charms of Zenobia for still another landscape. Once a year we packed ourselves up and drove to Gulf Shores, where we stayed for three weeks in a cottage belonging to old Doctor Beaupré. The cottage had a private footpath across the dunes to the beach, and its own bathing cabaña. It was there that Charles taught me a few things, himself: how to tie my shoelaces, how to make a Dagwood sandwich, how to swim in the surf. Slippery with sun tan oil and insect repellent, smelling of coconut, vanilla and sandalwood—-me and Nessa and Edgar Lee built elaborate sand works on the beach and cheered as the tide washed them away.

We were on holiday, and all the rules and arrangements of our everyday lives were temporarily put aside. Out from under Mam’s eye for this brief hiatus each year, Charles's worry lines disappeared and Lu-Esther laughed at things we kids said with an odd, off-kilter giddiness, as if she couldn't get over how clever and endearing we were. Sometimes, after dinner we’d play Spy, hiding and training the binoculars that were used for bird-watching and moon-gazing on our mama and daddy instead, as they sat on the creaky porch swing. To see our parents holding hands was enough to send us over the moon; it was a feeling like no other. It's what I’ve always imagined pure unadulterated bliss feels like.

Without any rules to govern us we tracked sand in the cottage and left our wet bathing suits hanging over the porch rail, stayed up late to catch fireflies till we dropped from exhaustion and had to be carried to bed. On rainy days there were games of Monopoly and Chinese Checkers, and each night Lu-Esther told ghost stories while mosquitoes whined against the screens and salt breezes dispersed them. All the while, somewhere out there across the Gulf, floated rumors of volcanic islands strung like pearls on a necklace and inhabited by dark-skinned people who spoke other, musical, tongues. These were the sacred precincts of childhood and family life, now nothing more than a series of grainy snapshots, remembered as perhaps too perfect.

So it was three places, then—-New Orleans, Zenobia and Gulf Shores—-that made up the limits of the known world for me as a child, and I felt a fierce attachment to them. Uncle Erskine was suggesting that the world was bigger than the comfortable, circumscribed one I knew, and he meant to show it to me. (End of part 1)

Chapter 23, Part 2, continues in the next issue where you’ll find out why Erskine tells Temple, "…you are one unto yourself…”

###

MEANDERINGS “Cardicide”

Recently, I received in the mail an often repeated request for a donation from a national charity/organization that was, as usual, accompanied by a set of generic greeting cards. While hurriedly perusing them, I inexplicably remembered my mother chastising me, “Barbara, there are starving children all over the world who would love to have the food that that you’re leaving on your plate.” That was the original seed that would be fertilized in so many different ways --- leading to this particular quandary.

Raised in a strict Catholic home and educated by both the Sisters of Mercy and the Jesuits, I am always a prime candidate for guilt. This psychic thorn pinches my spirit every so often via USPS. The “world of charities” has enshrined my name and home address on its list of guilt givers. Tangible evidence of the full-on guilt assault is the four drawers filled with greeting cards –four drawers, and I’m in need of a fifth (drawer, not scotch).

Here’s a small sampling of the charities who hope to reap the benefits of Murf’s guilt: SAGE, Fountain House, IFAW, Kids Helping Kids, Sierra Club, EDF, Americares, Habitat for Humanity, World Wild Life, AJWS, Cohen’s Medical Center, US Holocaust Museum, St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital, NSAL, National Audubon Society.

Why greeting cards? To what are they appealing? Why not just simply ask for a donation? Obviously, ageing guilt compels me to keep the cards. (Who knows; they could have been created by the grandchildren of those starving kids of long ago.) And, trashing them seems like “cardicide” to this senior “good girl.”

However, something keeps me from sending a requested donation, usually ten to fifteen dollars. My guilt is tripled even though I’ve done a bit of research and have learned that, in most cases, the charity receives only three to seven percent of the donation. The remainder goes to all the production, promotion, and administrative costs and fees. So, my ten dollar donation nets Charity XYZ the mighty sum of thirty, up to seventy cents. (Yes, I’m also aware that the production and distribution of these cards also provides jobs for many people. But, please, I just can’t go down another spiral of guilt.)

So, what to do with this increasing tide of greeting cards? Google search floats an ocean of things to do with used/unused greeting cards. Among them are:

· Make a book, tree, puzzle, gift box or bowl, bookmark, picture frame, place card, placemat, gift tag or bag, bunting, wreath. (Sister Mary Elizabeth would be so proud.)

· If that isn’t appealing, consider donating them to local prisons, rehabilitation centers or other state-run facilities because these entities often have craft times. (Try finding one that is within your locality OR one that has “craft time.”)

· How about taking them to a hometown Retirement Center or Day Care Center? They will use them for craft projects which they may sell in their “gift shop.” (Sure they will; plus, I’ll have the opportunity to buy a paper chain made of my donated cards.)

All things considered, the port of last resort may be my village’s recycling center where I’m certain I will meet other “collectors” depositing their greeting cards or the “artistes” who are there netting the discarded greetings for creating wreathes for the upcoming winter season.

Choices, always choices. And, then, there are those other donation requests with enclosed name labels, memo pads, nickels, pennies, dimes, medals. &

###

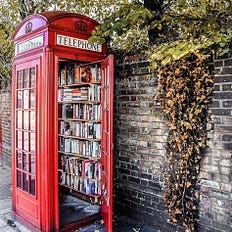

HYPATHIA’S BOOKROOM

A New Kind of Library

This week’s Bookroom column is a bit different. I’d like you to meet a true word/world voyager whose ideas will expand your spirit and polish your soul.

Dick Andres: Math teacher with a Ph.D. in English, textbook writer, Golf Magazine contributor, guy with a Hemingway beard and an infectious laugh, math mentor who is also a published poet. Allow me to introduce you to Richard Andres, a true renaissance man who walks through life with a very special perspective:

It is obvious that, for each of us, language is our hive, our nest, and that our quintessential behavior in that nest has been endless shared conversations about our being here, what we know, and how we survive. Furthermore, it is our very DNA that says we must talk to each other and figure out the world.

To that end, our symbols are the genes of civilization, of knowing, sharing, and transforming all sensory input into some creative response.To be sure, in each newly-forged image, equation or formula, the unexpected metaphors in art and science conspire in helping us to know what is the essence of the world (Gaia), the universe, and of all that is real.

Quotidian

The beginning is always simple:

through a crack in the blinds

the rhythmic bars of light walk the walls,

and I gather myself for breakfast

with grapefruit, coffee, hash browns burned,

bacon and eggs and toast,

and sunrise.

And I watch as seagulls carrying sunlight on their backs

sail up on the roof and with eager, raucous voices,

sit gossiping on the ridge beam overhead.

I open the wooden screen door

and set out like some beachfront Thoreau

walking barefoot in the cool morning,

feeling the sandpaper rub of the beach,

and the accidental touch of slick seaweed

sprawling up past the near edge of surf.

Further along the beach

beyond where the jetty-stones bivouac,

I hear and see the soft waves of the Sound

licking the shell of a horseshoe crab,

poking at the empty homes of mussels and periwinkles;

and once again, the north shore’s rough receding tide has revealed

a dozen of the rounded edges of random cobble–stones

from the days when freighted schooners would drop ballast.

Later on, while the warm noon sun is enameling

the red and green

of beach plums and sawgrass and bayberry,

I’m surprised by the screaming joy

of a sky-scrubbing brace of Suffolk hawks

sailing on thermals high above the curving bluffs

and playing off each other’s feathered arabesques.

Captured as I am in this sensory composition,

and seeing how I must be both a part of and yet apart from,

it is clear that the rhythm and sounds here

are all the music that no one has ever played

but that no one can help hearing.

R.J.Andres

Silence

Life can only be understood backward, but it must be lived forward. -S. Kierkegaard

Silence is always before,

is the shock of dawn gripping the water.

Silence is the rising sun rousting the wet grass and spilling light on leaves,

is the barely glimpsed deer in the deep shadowed woods

listening and waiting on the wind,

and the very moment before falcons dive

stitching sky to ground.

Beginning in the gray light of pre-dawn,

for a few hours I sit in a Jon boat

out in the middle of the lake

and cast long whispering lines and lures

that hang for a time before striking centers and circles.

In the softness of midday there is the calling song of cardinals

leaving hopeful silences before and after,

and the quiet stalled surprise of mating dragonflies

laddering on the air.

The color of silence is the warm earth waiting for rain,

the raw leaves of spring wet and greening,

the orange yawning of lilies in the garden,

the red of roses and tomatoes tugging at the sun,

and the white fall of a heron’s feather.

Before sunset, walking on the shore, circling round the curve of the lake,

I see the heron’s feather now floating on the still surface,

the bare spines of trout left on the shallow edge,

and lying in the thin grass

is a bird’s skeleton with bones like lace,

each are vivid signs of fossil poetry

telling me how much after implies the love songs of before.

R.J.Andres

You can read more of R.J.’s musings and poetry in the online magazine Arts and Opinion. His most recent poem is in the current issue at http://www.artsandopinion.com/2023_v22_n3/

###

I too, read the David Brooks article on connecting with others, and thought it was so important. To really see another person as we live our lives is something that may not happen as people rush around. So I appreciated your sharing of that, Barbara.

And it's interesting how Lea shares how she associates her fascination with guns to lovers!

That "outfilt" is meant to do everything wrong with what anyone would want, and of course, on purpose. Let's totally hide the model's body! Let's make it disturbing with the loose wires on the top right! Zero in terms of referencing the female body. It really is an anomaly in fashion and yes, worth noticing...