QUIDDITY, 56

WAR BABY, 32; plus "Meanderings" and "Hypathia's Bookroom"

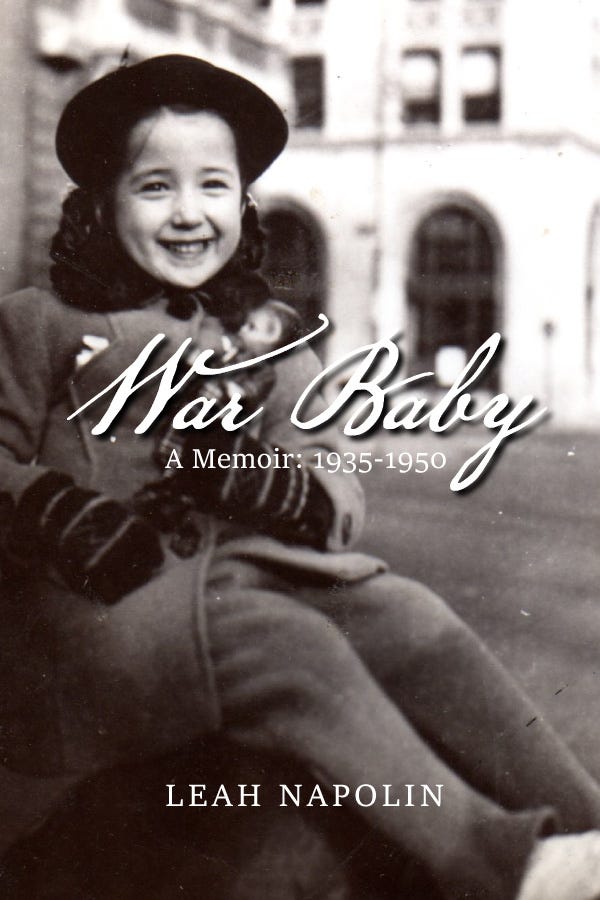

I wrote War Baby for my children, grandchildren, and for anyone else curious about a time not to be forgotten. I wrote it to give them some sense of what it was like growing up in a particular place at a particular time, and how those events shaped me as a person. But, the past is a moving target. Someone with firsthand experience of an event who tells a second person about it no longer controls the narrative. That second person may, then, retell the story adding to it her own information based on reflection, opinion or hearsay. Even two people present at the very same event will often view it differently. So, how do you tease out the truth, which can mean different things to different people?” —Leah Napolin

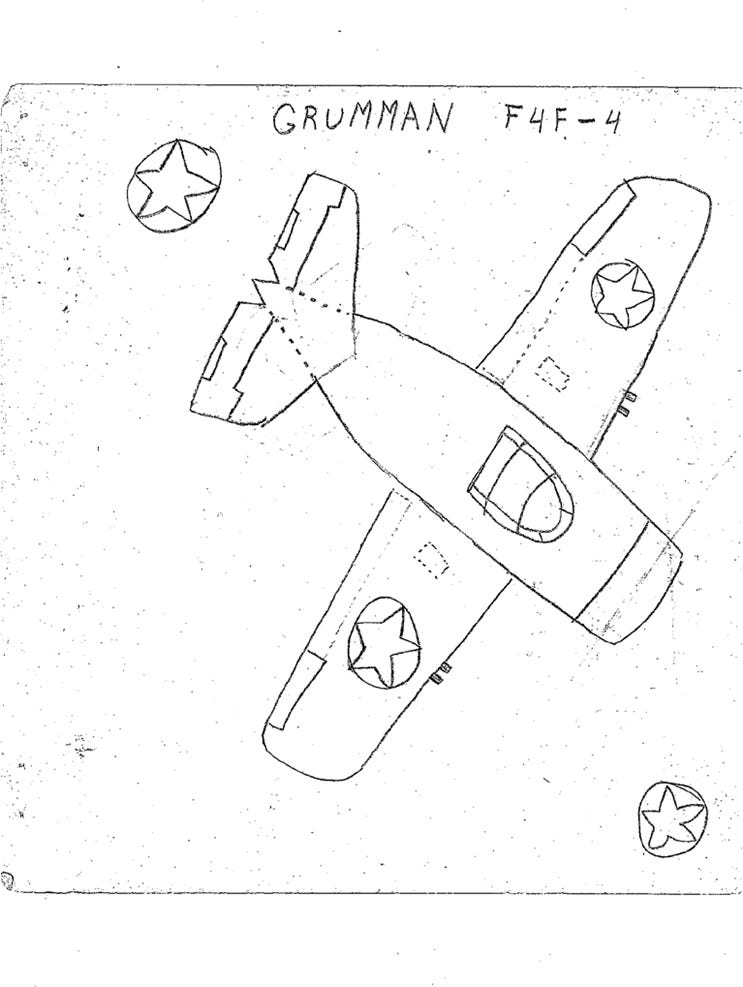

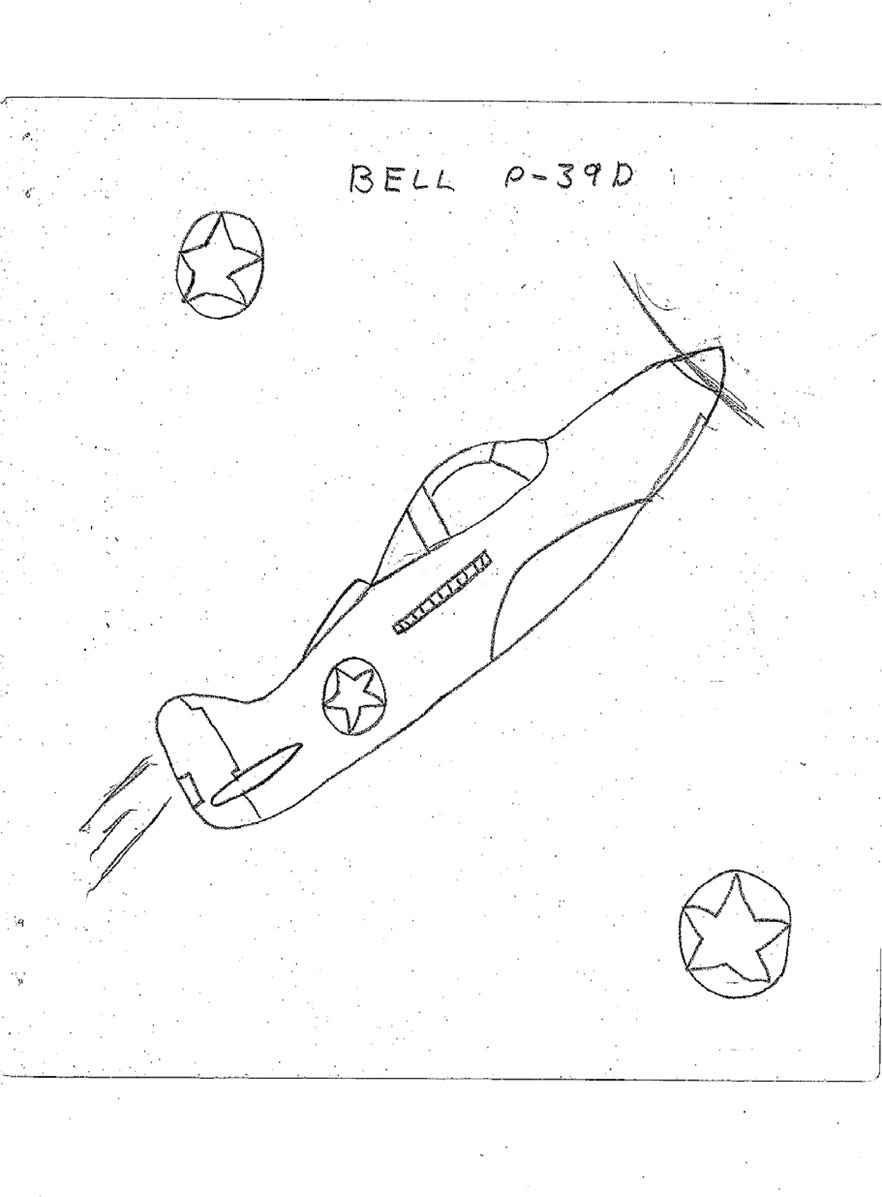

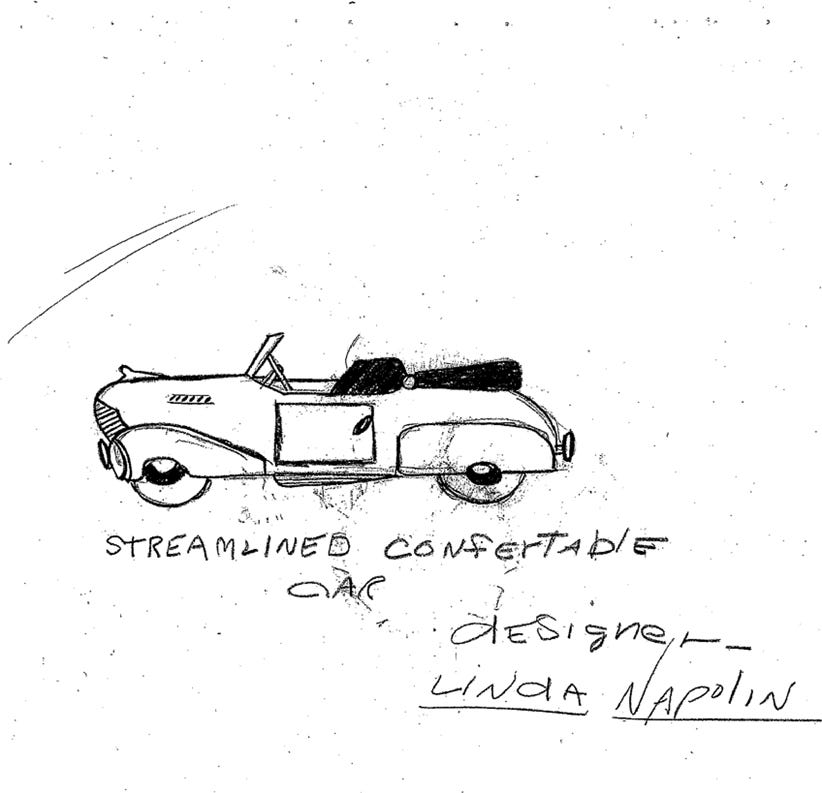

NOTE: Leah’s original print version of War Baby was a series of brief narratives or descriptions arranged alone on a single page and accompanied, at times, with related drawings she created during this time period, family photos, or WWII propaganda posters. Quiddity space doesn’t really allow for the images to be presented in a large format, but if you wish to enlarge an image, click on it, and an enhanced image will appear on the screen. Also, the language/idiom in this text is what this young girl would hear and use 1935-1950. (Today, May 13, is the sixth anniversary of Leah’s passing. Je t’aime, ma copine.)

***********************

PLAYING WITH THE ENEMY

In the months following the end of the war, a new girl enrolls in school and sits next to me in class in the very same seat where the Cootie Girl, now long gone, once sat. To look at her, scrubbed and blond and beautiful, leaves no doubt that she is an aryan member of the Master Race. She and her parents have just arrived on a plane from Germany. Where they were and what they did during the war is never mentioned, nor would it be polite to ask. They settle in Richmond Hill in a comfortable but modest house like every other house on their block. They speak excellent English but with a slight accent. Except for that, they blend right in.

The new girl invites me home where her mother greets me, warily I think. My own mother is faintly suspicious of them but chooses to be open-minded. I tell the new girl that I’m Jewish but she wants to be friends with me anyway—or, perhaps, given the eagerness with which she embraces me, because of it. I don’t know what to make of it. I can’t even imagine words like Auschwitz or Buchenwald coming out of her mouth. There is all this cruelty and bitter history swirling around us like storm clouds or black water circling a drain, but none of it seems to have touched her and it’s hard to think of her swept into the tide of it with her wholesome clear eyes and unquenched cheerfulness, so unlike Vera who carried her own cloud with her. We’re just two young girls who happen to like each other. And the war is over. Done. Or is it? As a sign of our friendship the new girl and I join the girls’ basketball team at a local church. I play forward, she plays guard. How upbeat is that? How American is that?

TWO WINGS AND FOUR WHEELS

After the war everything changes yet again, and my attention turns from drawing scenes of battle with tanks and airplanes to different makes of automobiles, sleek and futuristic, copied from the advertising pages of magazines filled with stories of domestic bliss and the thrill of being a consumer.

###

MEANDERINGS: “June 6, 1966”

I just finished reading Doris Kearns Goodwin’s memoir titled An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s which is an intimate history of a very public decade in which she and her husband Dick Goodwin played imposing and important roles in the administrations of JFK, LBJ and Senator RFK. A speechwriter for both the Kennedys and Johnson, Dick Goodwin was the primary writer involved in RFK’s famous “Day of Affirmation” address he delivered on June 6, 1966, to the students of the University of Capetown, South Africa. I bring it to your attention because it has so much to say to us at this particular juncture of worldwide events and of our own crossroads as a nation. I invite you to allow yourself the time to read and consider the ideals and principles advocated by this man who “would be President.” (I’ve cut the speech to fit this column’s space limits.) To read or to hear it in its entirety, click here.)

This is a Day of Affirmation -- a celebration of liberty. We stand here in the name of freedom.

At the heart of that western freedom and democracy is the belief that the individual man, the child of God, is the touchstone of value, and all society, all groups, and states, exist for that person's benefit. Therefore the enlargement of liberty for individual human beings must be the supreme goal and the abiding practice of any western society.

At the heart of that western freedom and democracy is the belief that the individual man, the child of God, is the touchstone of value, and all society, all groups, and states, exist for that person's benefit. Therefore the enlargement of liberty for individual human beings must be the supreme goal and the abiding practice of any western society.

The first element of this individual liberty is the freedom of speech; the right to express and communicate ideas, to set oneself apart from the dumb beasts of field and forest; the right to recall governments to their duties and obligations; above all, the right to affirm one's membership and allegiance to the body politic -- to society -- to the men with whom we share our land, our heritage and our children's future.

Hand in hand with freedom of speech goes the power to be heard -- to share in the decisions of government which shape men's lives. Everything that makes man's lives worthwhile -- family, work, education, a place to rear one's children and a place to rest one's head -- all this depends on the decisions of government; all can be swept away by a government which does not heed the demands of its people, and I mean all of its people. Therefore, the essential humanity of man can be protected and preserved only where the government must answer -- not just to the wealthy; not just to those of a particular religion, not just to those of a particular race; but to all of the people.

And even government by the consent of the governed, as in our own Constitution, must be limited in its power to act against its people: so that there may be no interference with the right to worship, but also no interference with the security of the home; no arbitrary imposition of pains or penalties on an ordinary citizen by officials high or low; no restriction on the freedom of men to seek education or to seek work or opportunity of any kind, so that each man may become all that he is capable of becoming.

These are the sacred rights of western society. These were the essential differences between us and Nazi Germany as they were between Athens and Persia.

And most important of all, all the panoply of government power has been committed to the goal of equality before the law -- as we are now committing ourselves to achievement of equal opportunity in fact.

We must recognize the full human equality of all of our people -- before God, before the law, and in the councils of government. We must do this, not because it is economically advantageous -- although it is; not because the laws of God command it -- although they do; not because people in other lands wish it so. We must do it for the single and fundamental reason that it is the right thing to do.

We recognize that there are problems and obstacles before the fulfillment of these ideals in the United States as we recognize that other nations, in Latin America and in Asia and in Africa have their own political, economic, and social problems, their unique barriers to the elimination of injustices.

In some, there is concern that change will submerge the rights of a minority, particularly where that minority is of a different race than that of the majority. We in the United States believe in the protection of minorities; we recognize the contributions that they can make and the leadership they can provide; and we do not believe that any people -- whether majority or minority, or individual human beings -- are "expendable" in the cause of theory or policy. We recognize also that justice between men and nations is imperfect, and that humanity sometimes progresses very slowly indeed.

If we would lead outside our own borders; if we would help those who need our assistance; if we would meet our responsibilities to mankind; we must first, all of us, demolish the borders which history has erected between men within our own nations -- barriers of race and religion, social class and ignorance.

###

HYPATHIA’S BOOKROOM

A New Kind of Library

“I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of a Library.” –Jorge Luis Borges

QUIDDITY, is building its own library of books that are of importance to us--intellectually, emotionally, spiritually, ethically, etc.-- books that we would definitely rescue from a trash pile. We’re calling it Hypathia's Bookroom after the chief librarian of the ancient library of Alexandria. Tell us the title, author, category, and why this book is important to you. Questions you might consider include: Would you read this book again? Would you gift it to someone (who, why)? What note would you write on the cover page?

On the shelves so far: The rescued books selected by readers has grown and takes up too much space to list them all here. You can peruse the entire listing by going to the blog section of my website at blmurphy.com.

"There are so very many books, and we have forgotten almost all of them." (Lit.Hub) May we save all we can.

Kafka’s ideal of what a book should be: “An ax for the frozen sea within us.” (Sigrid Nuez interview in “By the Book,” NYT Book Review, 12/10/23)

**********

(Carl L.) Via the stories of 6 different survivors, Hiroshima by John Hersey tells of the horrifying, immediate aftermath of the atomic bomb being dropped by the United States on this Japanese city of 245,000 people (100,000+ killed, 100,00+ injured). Most of us are only aware that the bomb ended WWII and saved the lives of thousands of American soldiers. But, in only 152 pages, Hersey recounts the human side of the explosion: the emotions, the injuries, the recovery and rebuilding. The experiences of six everyday people who survive the blast allow the reader to become aware of some of the realities of what happens to flesh and bone, individuals and families, hope and the future. As a wake-up call for the entire globe, Hiroshima should be required reading.