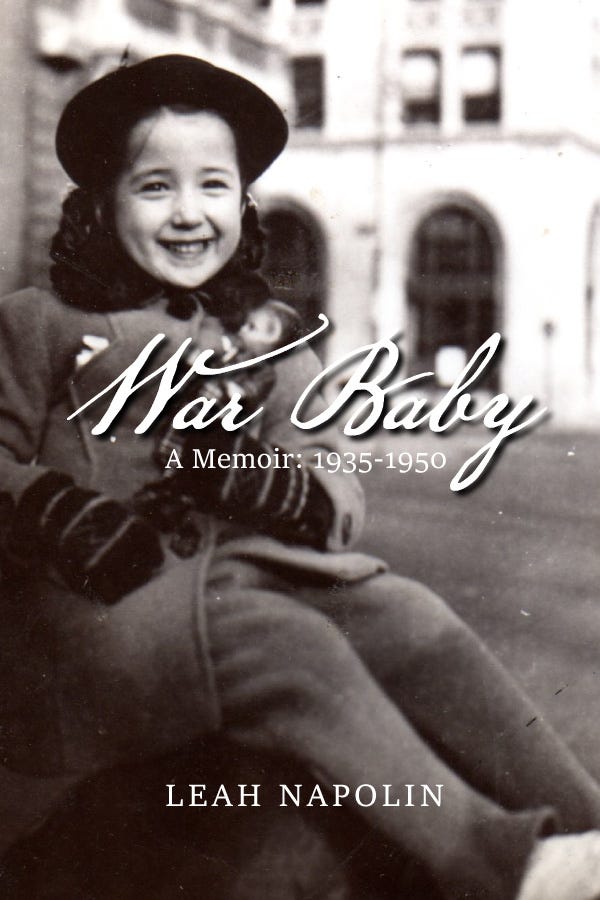

WAR BABY

I wrote War Baby for my children, grandchildren, and for anyone else curious about a time not to be forgotten. I wrote it to give them some sense of what it was like growing up in a particular place at a particular time, and how those events shaped me as a person. But, the past is a moving target. Someone with firsthand experience of an event who tells a second person about it no longer controls the narrative. That second person may, then, retell the story adding to it her own information based on reflection, opinion or hearsay. Even two people present at the very same event will often view it differently. So, how do you tease out the truth, which can mean different things to different people?” —Leah Napolin

NOTE: Leah’s original print version of War Baby was a series of brief narratives or descriptions arranged alone on a single page and accompanied, at times, with related drawings she created during this time period, family photos, or WWII propaganda posters. Quiddity space doesn’t really allow for the images to be presented in a large format, but if you wish to enlarge an image, click on it, and an enhanced image will appear on the screen. Also, the language/idiom in this text is what this young girl would hear and use 1935-1950.

***********************

SHLUF GEZUNT

“Tell me how you met Daddy.”

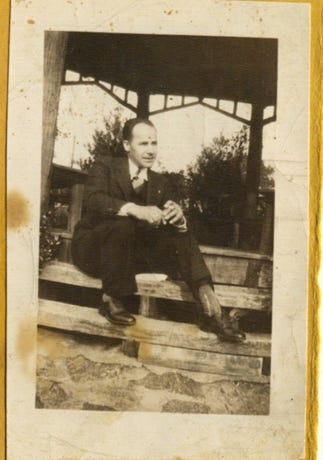

Oh, I’ve heard the story many times and Mother must be tired of telling it, but I never tire of hearing it. Each time she dutifully starts at the beginning. She was vacationing at a Jewish resort in the Poconos, not the Catskills—a young adult camp, the boys and girls in several large tents and rustic cabins. Her sisters and brothers and their friends and friends’ friends from school and work. Wholesome fun and camaraderie. She keeps photos of the boys doing stunts to show off, balancing on each others’ shoulders to form pyramids; the girls in admiring, affectionate clans, clowning around. That’s Mother, on the far left.

This was long after she had to turn down the scholarship to the Pennsylvania Academy of Art. Now she was a working girl, and it was from one of these fun-filled weekends that Mother left to go back to her job in Philly. She was at the railroad station waiting for the train when she noticed a man standing all the way at the other end of the platform. She looked away, glanced at her watch. The next time she looked in that direction the man was closer, maybe half the distance away. She turned away again; he was a stranger and she didn’t want to give him the wrong idea, didn’t want to appear forward. When she ventured to look a third time, to her surprise the man was standing on the platform only a few feet from her. He was friendly, well-spoken, tipped his hat and struck up a conversation.

“My name’s Moe,” he said.

He was from New York—handsome and older than the young men at camp, many of whom liked and pursued her, boys in their straw boaters whom she felt it was impossible to take seriously

Before the train arrived they exchanged information and agreed to meet again. Four months later they were married.

I love that story for the romance of it and the element of chance that brought them together. Two strangers on a train platform. A mysterious force called Fate, which can be both kind and cruel, draws them to each other. Each time I hear this story it deepens my sense of personal history and mercifully spares me from the reality that these two strangers formed the most imperfect of unions, from which I sprang. Not all marriages are made in heaven.

Even though Dale Judith goes to bed early and I go to bed late, Mother spends time with each of us saying goodnight. After the How-I-Met-Your Father story she leans over, kisses us and closely, intimately, whispers, “Shluf gezinteheit, meine kindt, shtay uf gezinteheit, sleep tight and happy dreams to you-you.” To me this is still a foreign tongue but to her it’s the language of the heart. Not just a language for keeping secrets and telling jokes but for expressing a tender thought, a parent’s blessing—and when used at bedtime makes me feel safe. Loved.

“What does it mean,” I ask?

“It means ‘go to sleep well, my child. Wake up well,’ ” she says. “Do all mothers say it?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” she replies. “But I do.”

She says it because of a popular goodnight prayer she grew up hearing, which upsets her. A prayer common in Christendom.

Now I lay me down to sleep

I pray the Lord my soul to keep And if I die before I wake

I pray the Lord my soul to take.

“How awful!” she exclaims, and goes on to reflect that the prayer might be about salvation but it’s spoken by a child, an innocent child. To acknowledge that your child might die is awful, she thinks. To imagine that the Angel of Death might swoop down at night and fold the sleeping child in its wings is awful. “We don’t say that,” she goes on, impassioned, her eyes shining with tears. “I won’t say it. When we toast, we say ‘L’Chaim! To life!’ I put you to bed at night with only happy thoughts of waking up in the morning. Good thoughts of sweet dreams, love, and long life. Yes, life!”

###

MEANDERINGS: “Four Spoons and a Round Table”

Something disquieting happened while composing this “Meandering” column.You’re reading or listening to the final draft of six versions of “Four Spoons and a Round Table.” I had planned to write a light-hearted recollection of a dinner with three dear friends during my visit to southern California a couple of weeks ago. All was going well until I read an article in The New York Times about a message the new Executive Editor of The Washington Post sent to his staff. Included in that issue of The Times were the ever present reports on the current administration’s latest actions and executive orders that furthered the anti-woke assault and the purging of D.E.I. Probably because I was in a mellow, memory-centered state-of-mind, the impact of these news stories unleased a fit of anger, frustration, and disbelieve. As a result, you’re reading a mix-up of both the personal and the political.

By now, you’re probably familiar with my two mantras: “The personal is universal,” and “The personal is political.” You’re also familiar with my meanderings often being set in motion by a casual remark, event, or visual.

And so: In his recent e-mail to the Post’s staff, Matt Murray stated that he was separating the production of the print newspaper from the rest of The Post and changing the organization of its newsroom. Specifically, he is quoted as writing, “Text will no longer be a default and length no more a measure of quality.” On an ordinary day and under ordinary circumstances, this remark would have generated a quick and shallow, “Is he serious?”

I was in the middle of remembering a dinner in the California desert, and this executive editor’s note pushed an “Oh, really?” switch in my brain. Just what does he mean when he says TEXT?”

Mr. Murray, are you asserting that a newspaper’s primary means of communication will NOT be words? Are you serious? Perhaps you feel pressured to enable anti-wokeness and further the annihilation of D.E.I. Perhaps, you’re allowing for the expansion of TEXT to include deriving meaning from photos, videos, movies, paintings, sculpture, instrumental music, clothing, sign language? Or, would you be fearful that I am accusing you (and others like you) of being too woke, too DEI? Whatever the case, thank the goddesses of journalism that I’m not a Post staff member. I’m an English instructor whose courses were presented within the framework of deconstruction, post-colonialism, feminism, structuralism, etc. And, no matter through what lens you view the world, facts are always facts. Words are words.

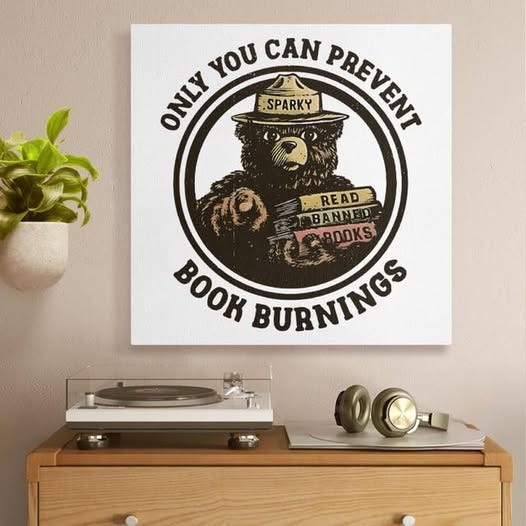

In the current climate and context of anti-wokeness and the purging of DEI, words are being criminalized and deleted. Books are being banned. I can’t ignore the suspicion and possibility that even a description of dinner around a round table could be ordered deleted, banned, or deemed illegal. This propels me to ask the Executive Editor of The Washington Post (and others who find Mr. Murray’s dictum acceptable) a few questions from the perspective of my categoried world.

Is my desert dinner no longer a simple gathering, but rather a complex political event?

With this in mind, my previously planned recounting of this long-anticipated dinner with dear friends will use the “default of text” + spoons + a round table, and a mixed berry cobbler in a plastic bowl. Would this be acceptable, Mr. Murray?

Picture it, Matt: Four lesbians of a certain age holding hands as the bristled shadow of a giant cactus drapes the echoed setting sun across a round table. Mary Oliver would be proud. (Oh my, Mr. Murray, does referring to my favorite member of the Lesbian Dead Poets Society make you uncomfortable? Well, buckle up; it’s going to be a bumpy ride.)

Dinner begins with eight hands of a certain age joined around the table with a prayer of thanksgiving being invoked by the four friends: two of whom are intimate friends of mine. Those entwined hands are what capture my attention, and I focus on them throughout the meal. These hands that have gone from strong, willful, curious, flexible extensions of goals and desires to veined, knuckled, sinewy hands that may have lost their strength but not their purpose, outreach, and determination. They are the tools of legacy. They are the hands that held the signs as we marched for our rights, for peace, for equality. They are the hands that held each other as we grieved, as we loved. The hands that wrote lesson plans, essays, poetry, letters, screenplays, grant proposals, books, eulogies. The hands that lifted us up, that planted the tomatoes, that held umbrellas over our heads, that erased blackboards in Pakistan, that stacked wood, that fed us chicken soup. Whether holding a pen, a camera, a shovel, a brush, a passport, these are hands that have touched thousands of lives, that have made a difference, that will not capitulate.

Mr. Murray, because we are text and use text, do you and your cohort feel that you and the rest of the world are endangered because so many students and colleagues were taught and led by these four lesbians? Do you fear for the safety of the environment because lesbians have been leaders in conservation and environmental studies? Do you fear that the future of world peace is threatened because four lesbians are involved in demonstrating for it? Is the love that each of us feels for the other somehow or other poisonous? So dangerous that you would consider it your obligation to ban, bury or burn any mention of them? Or, would you feel more comfortable with just photos or videos of our hands growing older, becoming thinner, more calloused, more bruised, more veined, some with wedding bands. But, Mr. Murray, they are pictures of resolve, of courage, of perseverance. How would you be able to hide that?

From the kitchen comes, “Does anyone want her own bowl for the mixed-berry cobbler?”

“Not really. We just need four spoons. We can eat dessert from the serving bowl. We’re all longtime friends here.”

Mr. Murray, if you did somehow consider publishing this, just where would you place it in The Post? Politics, Opinions, Style, Investigations, Climate, Well+Being, Business, Tech, World, D.C., Md.&Va., Sports? I’m afraid, Mr.Murray, you could situate us in any and all of them. You most likely would refuse to consider it. But, be aware, Mr. Murray, we ARE part of all of it.

The mixed-berry cobbler was delicious.