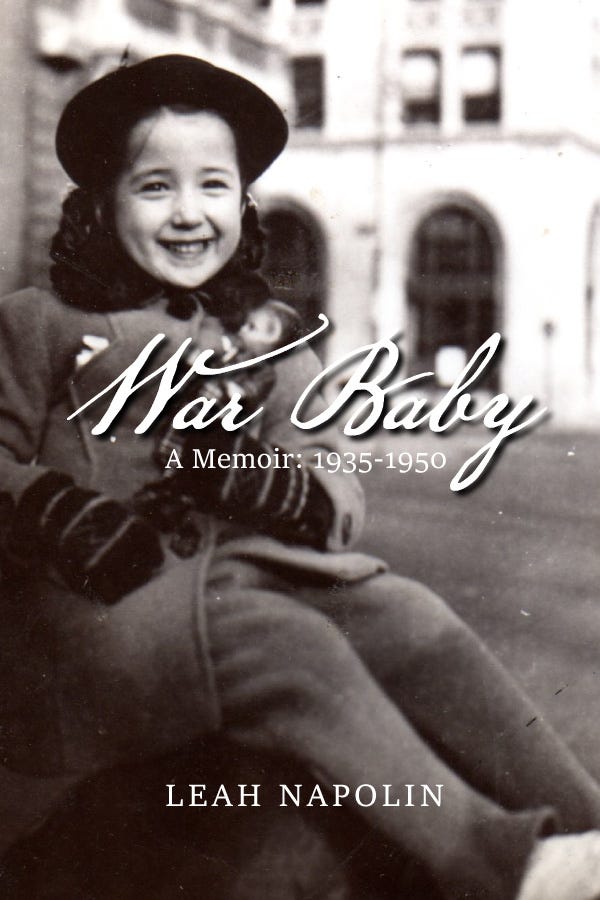

WAR BABY

I wrote War Baby for my children, grandchildren, and for anyone else curious about a time not to be forgotten. I wrote it to give them some sense of what it was like growing up in a particular place at a particular time, and how those events shaped me as a person. But, the past is a moving target. Someone with firsthand experience of an event who tells a second person about it no longer controls the narrative. That second person may, then, retell the story adding to it her own information based on reflection, opinion or hearsay. Even two people present at the very same event will often view it differently. So, how do you tease out the truth, which can mean different things to different people?” —Leah Napolin

NOTE: Leah’s original print version of War Baby was a series of brief narratives or descriptions arranged alone on a single page and accompanied, at times, with related drawings she created during this time period, family photos, or WWII propaganda posters. Quiddity space doesn’t really allow for the images to be presented in a large format, but if you wish to enlarge an image, click on it, and an enhanced image will appear on the screen. Also, the language/idiom in this text is what this young girl would hear and use 1935-1950.

***********************

YOU CAN TAKE IT WITH YOU (The final chapter)

I first learn about it when I see a poster go up in the halls of my school advertising the senior play. People are excited. “Please, can we go?” I beg my mother. It’s the last few weeks of my first and only year at Richmond Hill High. We’ve bought a house in the suburbs! We’re moving away! To a town called Sea Cliff. Part of me is relieved to be going because now I won’t have to imagine myself sinking to the bottom of the pool in shame and not graduating with my class, but part of me feels broken-hearted to leave this place with all its memories behind, the bad ones as well as the good. The truth is, it’s the precious precinct of childhood that I’m leaving. What awaits us, though, is a whole new chapter of life where we’ll make new memories and live happily ever after in a world without war, which I have at long last concluded is bad, not good. At the last minute, with the movers hoisting our piano onto the truck, I’ll grab the cigar box under my bed—the cigar box with its three tiny glass animals, all that’s left of the original dozens—and take it with me.

This will be only the second time I’ve seen live theater and I really want to go.

The first time was a disaster. It was a production at the Queens Playhouse of Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel. Mother and Hazel and Steven and I sat in the first row. Good seats, perfect sightlines. Standing on the apron of the stage on the other side of the orchestra pit not ten feet in front of us was the wicked witch. She began to sing. After a moment Steven cried out loudly “Oh!” and covered his ears. The witch could clearly see him. Playing a witch, she surely must have had moments when children in the audience would scream in fright, but this was different. The more she warbled her aria the more Steven crouched in his front row seat and carried on—moaning in distress, grabbing his knees and making panicky, pained faces. “Sh-h!” whispered Hazel. “Sh-h!” whispered Mother. It wasn’t the witch’s acting or witchy demeanor that was causing him distress, it was her voice. Just as high-pitched sounds at certain frequencies can set dogs to howling, the singer’s soprano was too piercing for Steven’s tender eardrums. Years later, he would tell me that it was like someone drilling holes in his head, and we laughed about it. The witch glared at us furiously, then tried not to, then glared again and for a moment swallowed the notes as her singing faltered. When we fled at intermission I sensed relief all around.

Tonight is only an amateur performance at an ordinary high school in a blended working class and lower-middle-class but upwardly-mobile lower middle class neighborhood in an outer borough of a big busy city—that reliable old standard You Can’t Take It With You, by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart. But it promises to be a happier event than Humperdinck.

The young actors go through their paces with enthusiasm; the audience loves it and them, their girls and boys, so sweetly poised and hopeful on the cusp of adulthood. I don’t cover my ears or make faces. On the contrary I feel astonished, enchanted! How did it happen that I’ve come full circle from fairy tales to fairy tales? At the curtain calls we cheer and stamp our feet and clap our hands wildly.

That was a good night. That was the night I found my true religion.

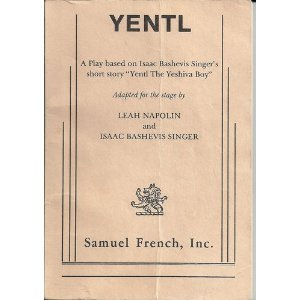

This is the final chapter of War Baby. I hope you have enjoyed peeking into the mind and heart of a young Leah growing into adolescence during WWII. Beginning with the next issue of QUIDDITY, you can expect a myriad of Leah’s other works of both fiction and non-fiction. Now, I have to choose which will be the first.

###

MEANDERINGS: “Aperçu”

This one-and-off event was excavated because of my latest trip to The Public Theater on Lafayette Street in the Village. Looking unsuccessfully for a free parking space, I found myself on Waverly Place. (Cue Streisand humming “Memories.”)

11 WAVERLY PLACE

Long ago, but not far away, before the West Village became the campus of NYU; before the gentrification of SoHo and the Lower East Side; and before E-Z pass and congestion-pricing, she lived at 11 Waverly Place, next to Eddie’s downstairs bar.

That day, she was pleased to have found a parking space close to the building and smiled to herself as she collected the mail. The apartment was a one bedroom on the first floor at the far end of the hallway. In fact, it was the only apartment on the first floor. Opening the heavy door, she came face-to-face with the bathroom door ajar and a pile of towels on the sink; turning to the right she glanced at the galley kitchen on her left and the living room straight ahead with a door to the bedroom. All the rooms lined up facing the building’s airshaft. Whether shared or alone, this was her home for the past couple of years.

She was looking forward to having a drink, a snack, and relaxing to some music in the living room, just as she used to do when they lived together.

After opening the bedroom’s only window, she prepped a gin and tonic to balance the heat of the mid-September afternoon with no air-conditioning. She turned on the fan and turned up the recording of Mozart’s Piano Trio in G which encouraged her to drift away from the demanding pile of essays she had to read that night.

Eyes half-closed with drink in hand and head against the sofa’s back pillow, she didn’t notice the man standing in the bedroom’s doorway.

It wasn’t his voice that broke her reverie. It was the splash of her drink in response to an aggressive piano flourish. She bent over trying to catch the lime and piece of cheese on her lap. That’s when she caught a glimpse of a pair of Levis next to the stereo cabinet.

She didn’t jump. She didn’t scream. She froze. The drink puddled in her lap as she stared at the guy. Without blinking or moving, she fixated on the fuzzy form that smelled of stale beer. “What the fuck is happening here?” she yelled to herself.

Balanced with one hand on the white door frame, he gurgled as if his mouth was filled with a slurpy.

“Shcuse me. Thanksh for openin that winda.”

Time seemed to stand still and she remembered all those times they had talked about getting window guards and their always putting it off. “We’ve got screens. Why don’t we just ask the super to install guards on the windows? I’ll ask him the next time I see him.” But, they never did.

“Please miss, don’t scream. Please don’t scream. I’m not gonna hurt ya. All I wanna do is get the hell outa here. I can see the door from here. I’ve been trapped in that damn well for I don’t know how long. Musta been really drunk when I climbed over that metal gate. Couldn’t climb out when I woke up. Hadda wait for somebody to open a winda.”

Holding up his arms while slowly backing unsteadily toward the door, he appealed to her, “Ya see, I don’t want nothin’. I’m just headin’ for the door. Please don’t scream or call the cops. I’m really not a bad guy.”

It wasn’t until he tried to unlock the door’s dead bolt that she moved. For some reason or other, she mumbled, “Turn the knob to the right.”

He did and was gone.

She didn’t go to the door; she didn’t yell or call the police. She was not sure what just happened. She was sure that she was okay. No bodily harm, no money stolen, no damage except for the bent screen in the bedroom. No reason to call the police and go through all the questions, the search, the paperwork. “What would I tell them anyway?”

I can hear it now: Hello. I’d like to report a break-in to my apartment. No, he’s gone. No, he didn’t hurt me. No, nothing was taken, No, there’s no damage. No, he didn’t threaten me. He was polite and thanked me for opening the window. I just wanted to notify the police in case he tries to do it again. Yes, I realize that since this isn’t an emergency, it’ll be a while for the police to arrive. And, if and when the cops do come? — Sorry, I can’t describe him other than he was wearing Levis and really stank from stale beer. No, I don’t know if he was white or Black. No, I don’t know if he had any facial air. No, the only thing I can tell you is that he wasn’t a giant or a midget. No, he didn’t have an accent other than a drunk slur. No, I couldn’t pick him out of a line up. No, I don’t think going down to the stationhouse to look at some photos would be helpful. Sure, I understand there’s not really anything you can do with so little to go on. Thanks for checking in anyway. Sure, if he comes back, I’ll let you know. — I can hear it now: An APB: be on the lookout for a smelly guy wearing Levis. And, I can see the headlines: Cops Stopping Men Wearing Levis and Smelling them.

Geeez. There’s no way I’m going to make an ass of myself.

It was just not worth her time, energy, and embarrassment. He’s always just going to be the smelly Levi guy who used her bedroom as a short cut to the street.

After checking the hallway and making certain the lock on the door was secure, she went into the bathroom, folded the towels, and sat on the toilet mulling over the past 5-10 minutes.

“Gotta clean up the mess in the living room.”

She sponged the rug and threw the shriveled slice of lime and fuzz-covered piece of cheese into the empty glass.

Noticing the damp and wrinkled stack of papers on the coffee table, she whispered to herself, “I can see it now. Sorry kids, a drunk snuck into my apartment last night, and I dropped my drink which kinda splashed on your essays. I promise to get to them over the weekend.”

Trying to reinstall the screen without success, she noticed an empty beer bottle lying on the concrete outside the bedroom window. “I’ve got to call the super tomorrow to fix the screen and pick up that bottle. One thing’s for sure though; I don’t think I can stay here tonight.”

With a fresh drink in hand, she reached for the phone.

“Someday I’ll laugh when I tell this story.” &

###

HYPATIA’S BOOKROOM

A New Kind of Library

“I have always imagined that Paradise will be a kind of a Library.” –Jorge Luis Borges

QUIDDITY, is building its own library of books that are of importance to us--intellectually, emotionally, spiritually, ethically, etc.-- books that we would definitely rescue from a trash pile. We’re calling it Hypatia's Bookroom after the chief librarian of the ancient library of Alexandria. Tell us the title, author, category, and why this book is important to you. Questions you might consider include: Would you read this book again? Would you gift it to someone (who, why)? What note would you write on the cover page?

On the shelves so far: The rescued books selected by readers has grown and takes up too much space to list them all here. You can peruse the entire listing by going to the blog section of my website at blmurphy.com.

"There are so very many books, and we have forgotten almost all of them." (Lit.Hub) May we save all we can.

Kafka’s ideal of what a book should be: “An ax for the frozen sea within us.” (Sigrid Nuez interview in “By the Book,” NYT Book Review, 12/10/23)

**********

The current federal administration is conducting what could be metaphorically described as a book burning. On March 31, 2025, by executive order, the staff of the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMS) was put on administrative leave. This would lead to ending the main source of federal support for our country’s museums and libraries Across the nation, private citizens and members of Congress have been signing letters and petitions in protest, including a petition sponsored by EveryLibrary and signed by over 21,000 people. — JOIN THEM!!

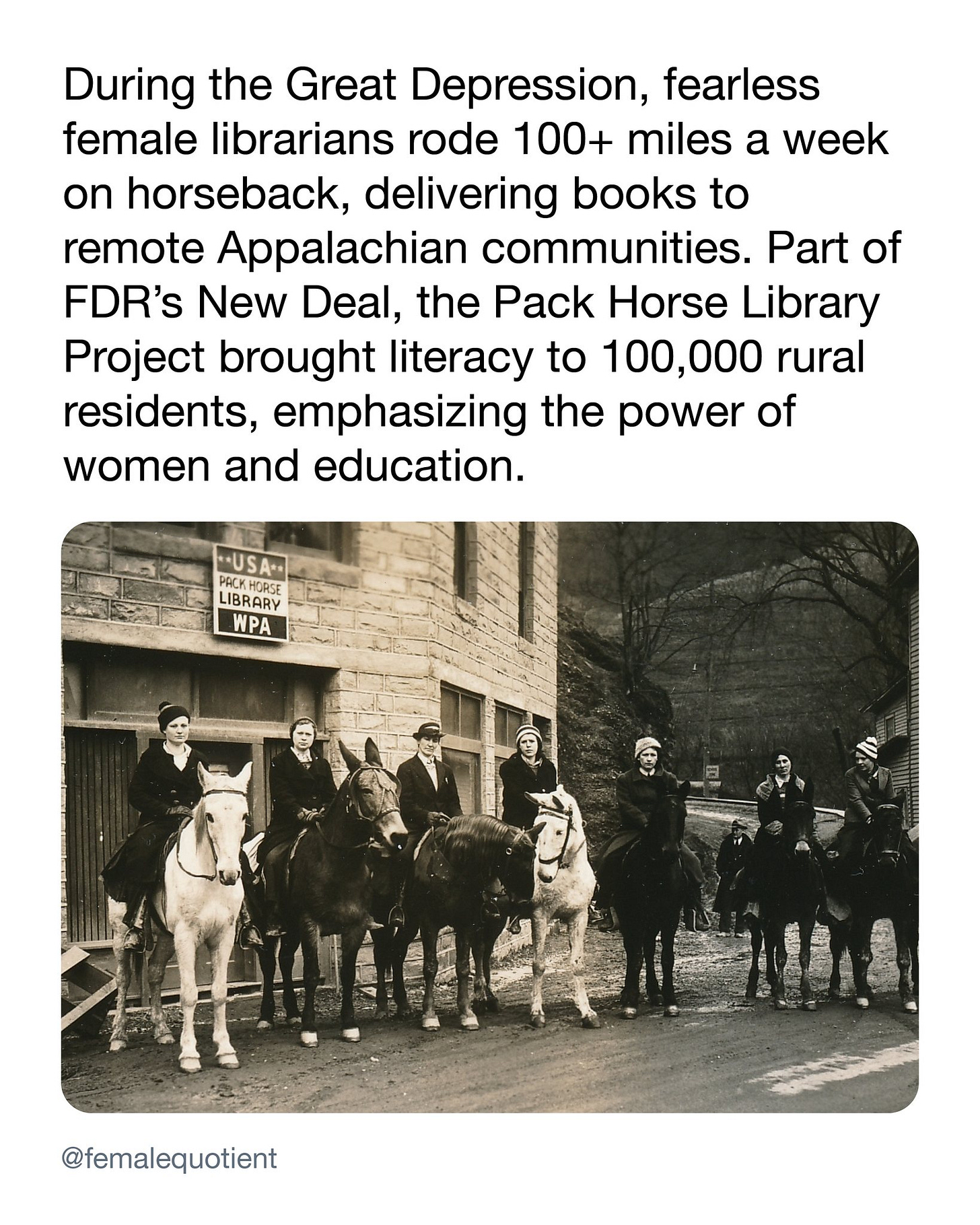

As an illustration of the determination of librarians (and those who support them) to provide access to books, consider the Pack Horse Librarians of the Depression Era.

Here are two recommended novels that will both capture your attention and introduce you to the trials, tribulations, goals, and loves of “book heroines.”

(Eileen O) One of my favorite things about Kim Michelle Richardson’s The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek (2019) was how much I learned of a time, place, and people of which I previously knew little. The story is set in the Appalachian section of Kentucky during the Depression with all the hollers and hidey-holes where the hill folk lived in almost utter isolation and gut-wrenching poverty. The main character, Cussy Mary, is a pack horse librarian working for the WPA bringing library books to the people living in those isolated places in the hills. These folks often lived in spots extremely difficult to reach, but, like all the real-life pack horse librarians, Cussy Mary had the grit and dedication to always complete her route. She also had a powerful love of books, reading, and learning and an overwhelming desire to share that with others who hungered for it as much as they did for food, which was seemingly in even shorter supply than the books.

(Lynne S) Based on a true story rooted in America’s past, The Giver of Stars by Jojo Moyes (2019) has two main characters: Alice and Margery. Alice is an English girl who moves to America with her new husband. She goes from English well-to-do strictures to living in a Kentucky coal mining town in the 1930s, and her husband is the son of the mine owner, a cruel man who rules his son's life. The son is handsome but something is wrong with him, something intolerable to a marriage. Out of sheer desperation and boredom, Alice bucks her family and takes a job riding books around for the WPA Pack Horse Library. The library is mainly operated by Margery, the daughter of one of the town's worst families. Think Hatfields and McCoys. She's a free spirit in a world where families kept to themselves, off in the mountains, miles from any school, likely with parents who were illiterate. This mobile library was the only hope for the literacy of some families. These heroic women refuse to be cowed by men or by convention. Although they face all kinds of dangers in a landscape that is at times breathtakingly beautiful, and at others brutal, they’re committed to their job: bringing books to people who have never had any, arming them with facts that will change their lives.